The Beauty Empire of Annie Turnbo Malone

As a true Entrepreneur, Annie said, "I went around in the buggy and made speeches, demonstrated the shampoo on myself, and talks about cleanliness and hygiene until they saw I was right."[2] In 1902 Annie moved to St. Louis, Missouri, to sell her product to a larger audience.[3] As the success of the product grew Annie moved away from personal direct sales to empowering agent-operators that she trained. She then created a relationship with these women, where she earned a portion of the products they sold and hair treatments they performed in their independent shops. Through this method, Annie widened the distribution of her product from a small regional business to a national and eventually international business.[4]

| |

|

The success of Annie Malone falls in the realm of what Leon Prieto calls a social entrepreneur. According to Prieto in African American Management History: Insights on Gaining a Cooperative Advantage explains how Annie used social entrepreneurship to "adopt a mission to create and sustain social value, pursue new opportunities to serve that mission, engage in continuous innovation, adaptation, and learning, and exhibit a heightened sense of accountability for outcomes created and to constituencies served." [5] Meaning Annie used a necessary and valued service in her community and turned it into an enterprise. At the peak of her life, it is estimated that Annie Malone's wealth was over 14 million dollars.[6]

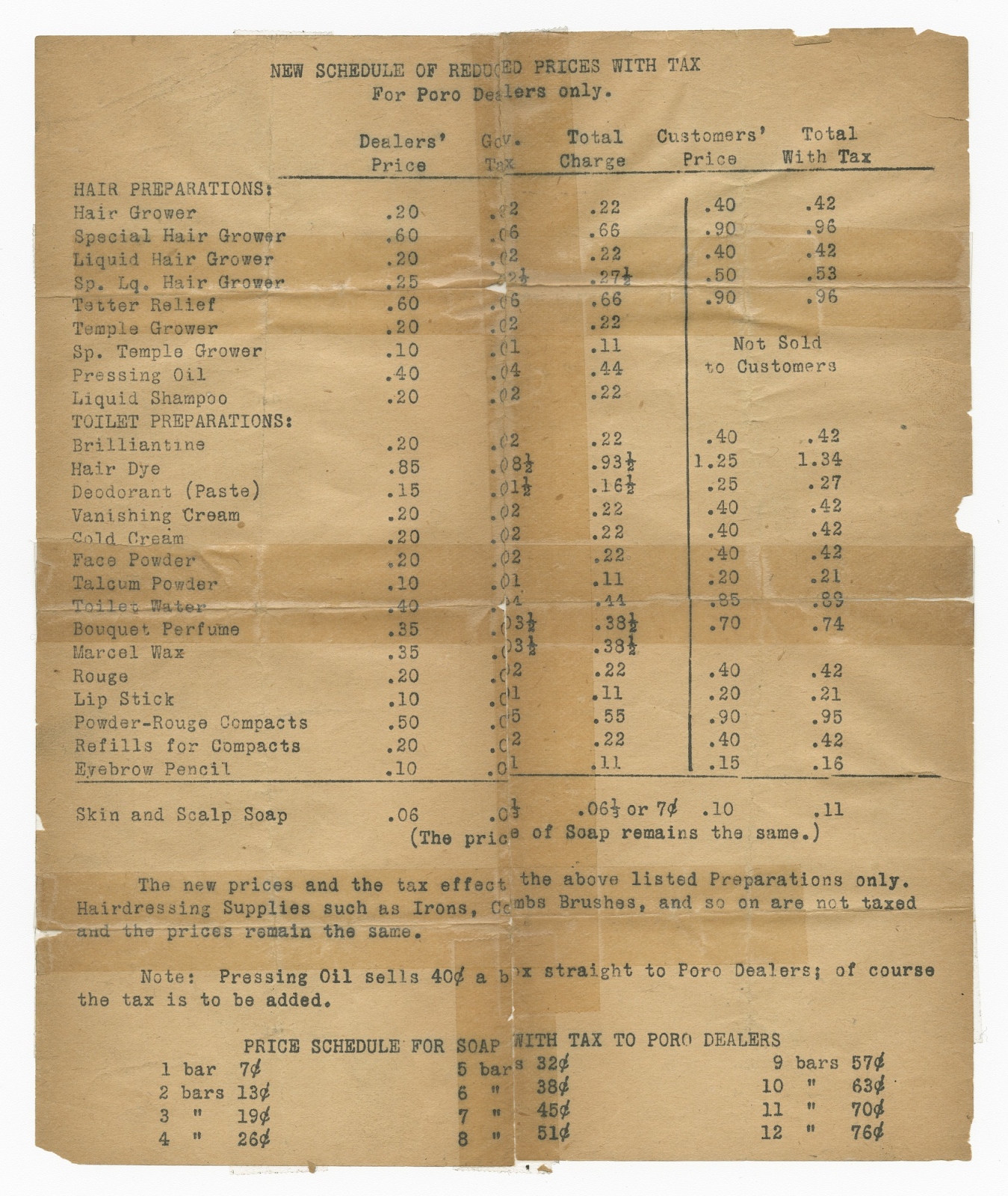

A large portion of Annie's success lies in the beauty school she founded in the 1900s, Poro College. While the primary purpose of the school focused on training women to create the hair straightening method that she invented, the curriculum did not end there. A graduate of the school learned how to dress for success, talk with confidence, and professionally conduct themselves. At the height of the college's success, Annie employed over 200 people just at the college. In addition, the franchises produced another 75,000 jobs for African American women when prospects were slim.[7] Her methods were not limited to America but expanded to Canada, Haiti, the Bahama, Africa, South and Central America, the Philippines, and Cuba.[8] Eventually, she moved her headquarters to Chicago, Illinois and by the time of her death, had over 32 beauty schools across the nation.[9]

|

| The broad ax. [volume] (Salt Lake City, Utah), 04 Dec. 1920. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. |

Annie's enterprise was remarkable for many reasons, especially since she was an African American woman in the early 1900s. At this time in American history, business models were switching from small family-owned businesses to large corporations, where a hierarchy in administration allowed exponential growth. Annie Malone grasped these changes and embodied them in her franchised enterprise. In The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business, David Landes discusses this very notion of a shift in business practices where costs were lowered, and production increased, allowing businesses to grow.[10] Those who adopted these strategies saw exponential growth, as evidenced by Annie's success.

Due to Annie Malone's success, she

turned around and used her wealth to strengthen and change her community. Often

when we hear the word philanthropist, we think of people like John Rockefeller,

but Annie Malone did just as much, if not more, to empower her community. Annie

lived a modest life in order to give back. She donated and helped create the first YMCA

for African American children. In addition, she generously donated to Howard

University College of Medicine and fully funded two students attending there

each year. She supported the St. Louis Colored Orphans Home, served on the

board of directors as president from 1919-1943, and was able to help them buy

their facilities in St. Louis.[11]

|

| The daily bulletin. (Dayton, Ohio), 06 June 1946. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. |

Unfortunately, the goodwill and

hard work of Annie Malone was not shared by those in her circle. Due to the

mismanagement by others, Annie Malone would eventually find herself and her

business in trouble with the IRS. Although she accomplished many incredible feats,

her later years were spent undoing her company's legal and financial trouble.

However, despite these troubles, the legacy of Annie Malone lives on in her

protegees like Madam C.J. Walker and the 75,000 other business owners she

helped over her years in business. While Annie Malone may not be as widely

known today as others, it does not diminish the accomplishments and foresight she

had in her time. Annie Malone is the epitome of an American rag to riches

success story that embodies the American dream, entrepreneurship spirit, and philanthropic notions of the

early 1900s.

Bibliography

Bailey, Diane Carol and Diane Costa, Milady Standard Natural Hair Care & Braiding. Clifton Hills: Cengage Learning, 2013.

"Black History Highlight: The Annie Malone story."

Explore St. Louis. February 5, 2013.

Houston, Helen R.

"Annie Turnbo Malone." The American Mosaic: The African American

Experience. ABC-CLIO, 2010.

Landes, David S. Review. Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in

American Business. Economic History Association. https://eh.net/?s=the+visible+hand

Miller, Rosemary Reed.

The Threads of Time, the Fabric of History: Profiles of African American

Dressmakers and Designers from 1850 to the Present. Washington, D.C.:

T&S Press, 2007.

Peiss, Kathy. "' Vital Industry' and Women's Ventures: Conceptualizing Gender in Twentieth-Century Business History." Business History Review 72, no. 2 (1998): 219-241.

Phillips, Evelyn

Newman. "Ms. Annie Malone's Poro: Addressing Whiteness and Dressing

Black-Bodied Women." Transforming Anthropology 11, no. 2 (2003):

4-17.

Poinsett, Alex. "Unsung

Black Business Giants; Pioneer Entrepreneurs Laid Foundations for Today's Enterprises."

Ebony (March 1990): 96-124.

Prieto, Leon C.

and Simone T.A. Phipps. African American Management History: Insights on

Gaining a Cooperative Advantage. Bingley, U.K.: Emerald Publishing Limited,

2019.

Principal

Register Trade-Mark, United States Patent Office. Chicago, Illinois, USA:

United States Patent Office. October 19, 1948.

"The Broad Ax." (Salt Lake City, Utah), 04 Dec. 1920. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

"The Daily Bulletin." (Dayton, Ohio), 06 June 1946. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

Weems, Robert E.

Jr. "A Star is Born." The Merchant Prince of Black Chicago. Chicago:

University of Illinois Press, 2020.

[1] Helen R. Houston, “Annie Turnbo Malone,” The American Mosiac: The African American Experience,ABC-CLIO, 2010.

[2]

Robert Weems Jr., “A Star is

Born,” The Merchant Prince of Black Chicago (Chicago: University Press

of Illinois, 2020), 58.

[3] “Black History Highlight: The Annie Malone Story,” Explore St. Louis (February 5, 2013): 24.

[4]

Kathy Peiss, "’Vital

Industry’ and Women's Ventures: Conceptualizing Gender in Twentieth Century

Business History," Business History Review 72, no. 2

(1998): 223.

[5] Leon Prieto and Simon T. A. Phipps, African American Management History: Insights on Gaining a Cooperative Advantage (Bingley, U.K.: Emerald Publishing Limited, 2019), 78.

[6] Rosemarry Reed Miller, The Threads of Time, the Fabric of History: Profiles of African American Dressmakers and Designers from 1850 to the Present (Washington, D.C.: T&S Press, 2007), 45.

[7] Diane Carol Bailey and Diane Costa, Milady Standard Natural Hair Care & Braiding (Clifton Hills: Cengage Learning, 2013), 83.

[8] Alex Poinsett, “Unsung Black Business Giants; Pioneer Entrepreneurs Laid Foundations for Today’s Enterprises,” Ebony (March 1990): 96.

[9] Ibid.

[10] David S. Landes, Review, Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Economic History Association. https://eh.net/?s=the+visible+hand

[11] Evelyn Newman Phillips, “Ms. Annie

Malone’s Poro: Addressing Whiteness and dressing Black-Bodied Women,” Transforming

Anthropology 11, no. 2 (2003): 11.

Comments

Post a Comment